Cpp for Embedded Systems Part 3: Hierarchical State Machines

Published on 3/20/2019

- A Hierarchical State Machine

- Ad-Hoc state machine implementation

- Designing the Machine

- Simple Turnstile Machine

- Hierarchical State Machine

- Deus Ex Machina (as Conclusions)

Hi there dear Software/Embedded developers, this is the 3rd part of a blog series about using C++ in software development for microcontrollers. In the first post I explained a technique that uses C++ templates and inheritance for the developing data structures that are allocated on the stack but can be referenced like if they were on the heap. In the second post in the series, I used those data structures to create a Signal and Delegate class that allows the use of one or multiple callbacks in a type-safe way.

This post is about developing a Hierarchical State Machine library with the following requirements:

- no heap

- no exceptions

- no external libraries

- C++x03

The need for those requirements has been extensible explained in the previous articles.

As a footnote (in the introduction ;-)), I’m an advocate for C++ in bare-metal applications but in all the examples I use prinft instead of std::cout, and you may ask: Why not C++ all the way down? Most architectures have a decent printf implementation some with limitations like, for example, you can’t print floats, meanwhile std::cout will eat your memory. So, I use printf in order to be able to copy and paste the code into a microcontroller without any stack overflow apocalypse.

In full disclosure, this library was developed with the help of Manuel Alejandro Linares Paez.

A Hierarchical State Machine

What is that?

Let’s first talk about “simple” State Machines formerly known as Finite State Machines because of the … finite states. These are the classical Computer Science and Electrical Engineering State Machines usually taught in Digital Electronics classes. This type of States Machines are often used to model several systems with clear states and outputs for every state. They are used from a simple turnstile control to a compiler lexical parser, and they help to keep the solution simple and auditable.

The Hierarchical part is a sort of extension to the concept in which the states can be nested in order to add encapsulation to them, it also introduces the concepts of onEnter/onExit that are actions that can be triggered when a state is entered or exited, and when used in conjunction with the nested states this type of actions are chained and several onEnter/onExit can be executed when the states are transverse from a parent to a child state, and vice versa.

For a comprehensive Hierarchical State Machine articles please read the Introduction to Hierarchical State Machines from the Barr Group, and for an entire framework solution read Miro Samek book Practical UML Statecharts in C/C++.

In the Computer Science and Software Engineering world, there is a similar concept to the State Machine know as the State Pattern. The differences are subtle, and the final implementation blurs the lines between them.

Ad-Hoc state machine implementation

Most of us have used what I like to call ad-hoc-on-the-fly-switch-case-state-machines, What I mean by this? Let use an example with a simple turnstile machine.

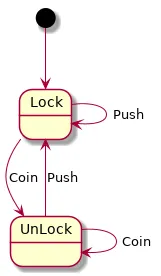

The turnstile state chart is like the “hello world” of the state machine designs, it’s simple and has all the features of a finite state machine: events, transitions, auto-transitions, and states. In the example there are two possible states Lock (initial state) and UnLock, and two possible events or inputs: Coin inserted and Push bar.

The system will be initially locked until the Coin event is dispatched, then it will be in this state until the user turns the turnstile bar which will dispatch the Push event and the state machine will transition to the Lock state.

Switch case statement implementation

#include <stdio.h>

using namespace std;

enum Event { Coin, Push };

enum States { Lock, UnLock };

void Dispatch(Event event) {

static int state = Lock;

switch (state) {

case Lock:

if (event == Coin) {

state = UnLock;

printf("Transition Lock -> UnLock \n\r");

} else if (event == Push) {

printf("Self transition Lock -> Lock \n\r");

} else {

printf("Event Error: %i is not a valid event!! \n\r", event);

}

break;

case UnLock:

if (event == Coin) {

printf("Self transition UnLock -> UnLock \n\r");

} else if (event == Push) {

state = Lock;

printf("Transition UnLock -> Lock \n\r");

} else {

printf("Event Error: %i is not a valid event!! \n\r", event);

}

break;

default:

printf("Error: %i is not a valid state!! \n\r");

}

}

int main() {

Dispatch(Push);

Dispatch(Coin);

Dispatch(Coin);

Dispatch(Push);

}

This is the terminal output:

Self transition Lock -> Lock

Transition Lock -> UnLock

Self transition UnLock -> UnLock

Transition UnLock -> Lock

The switch case pattern is a first approximation that sort of works for a very small state machine (note the lack of hierarchical in the machine), but the level of spaghetti code grow exponentially every time that you add a new state, event or transition. For the perhaps not well versed in the C/C++ inner workings, the declaration static int state = Lock; is interesting because of the static modifier in a local variable declaration, when a local variable is declared as static it behaves as a global declaration but with a local scope.

What did I mean by that? Well, in this case, the state variable is allocated in the data segment, which means that its value is first initialized in the Lock state and then the modifications are kept between function invocations.

Some of you perhaps say that the default and else statement can be deleted because there is no other state or event, but never underestimate the power of a well-motivated casting.

This type of implementation is relatively simple to remember just switch-case the states and if-else the events and is the got to pattern when you are in a rush or can’t use a 3rd party library.

Designing the Machine

So, What is the desired interface of a proper Hierarchical State Machine Library? I take the most inspiration from the Qt State Machine API, as I have mentioned before I’m a fan of the Qt framework and its implementation of most software patterns in C++, and the Hierarchical State Machine is not the exception. My framework takes Qt ideas and implements them with bare-metal restrictions.

There are two main classes the State Class and the Hierarchical State Machine Class, the first one represent the state, has 2 signals: entered and exited, that are triggered when the state is entered or exited, and also has two virtual methods onEntered and onExited that can be overridden in a subclass if needed. It also has an overload collection of addEvent methods in order to define the behavior of the state for every event that arrives.

In any particular state, an event can trigger an action and/or a transition to another state. In this context, an action is a Delegate with the void (int) signature. The state must also be able to hold an internal static allocated list of Events, this list is totally internal to the state machine operation.

The Hierarchical State Machine class must be able to add states, dispatch events, start and stop the event processing. In order to do this, it needs to modify the internal protected state of the states but without breaking the encapsulation. There are two ways to archive this in C++, one is to make the Hierarchical State Machine class a subclass of the state class, this has the inconvenience that the state machine will also have the internal list of events that are completely useless to the state machine, and it will consume memory that is precious in any microcontroller application. The other way to archive this is in using the hated but useful friend modifier :)

For a desktop application using protected inheritance in order to access the protected members of a class is the go-to solution, but this also is the classical criticism of inheritance by the functional programming folks.

Another questionable decision was the specification, using the C macro #define MAX_NEST_DEPTH 16, for defining the maximum state nesting. This size can be modified by redefining of the macro at compile time. In a newer library version the nesting depth will be specified via a state machine class template parameter.

Simple Turnstile Machine

Hierarchical State Machine implementation

#include <stdio.h>

#include "../../Include/HierarchicalStateMachine.hpp"

using namespace eHSM;

const int STATE_MAX_EVENTS = 2;

void OnPushedInLocked(int event) {

printf("Event: %i received\r\n", event);

printf("Self transition Locked->Locked\r\n");

}

void OnPushedInUnLocked(int event) {

printf("Event: %i received\r\n", event);

printf("Transition UnLocked->Locked\r\n");

}

void OnCoinInsertedInLocked(int event) {

printf("Event: %i received\r\n", event);

printf("Transition Locked->UnLocked\r\n");

}

void OnCoinInsertedInUnLocked(int event) {

printf("Event: %i received\r\n", event);

printf("Self transition UnLocked->UnLocked\r\n");

}

int main() {

enum Events { CoinInserted, BarPushed };

Declare::State<STATE_MAX_EVENTS> locked;

Declare::State<STATE_MAX_EVENTS> unlocked;

// actionHolder is a stack allocated Delegate that will be used to add actions to every events

State::Action_t actionHolder;

actionHolder.bind<OnPushedInLocked>();

locked.addEvent(BarPushed, locked, actionHolder);

actionHolder.bind<OnCoinInsertedInLocked>();

locked.addEvent(CoinInserted, unlocked, actionHolder);

actionHolder.bind<OnCoinInsertedInUnLocked>();

unlocked.addEvent(CoinInserted, unlocked, actionHolder);

actionHolder.bind<OnPushedInUnLocked>();

unlocked.addEvent(BarPushed, locked, actionHolder);

HierarchicalStateMachine hsm;

hsm.setInitialState(locked);

hsm.start();

hsm.dispatch(BarPushed);

hsm.dispatch(BarPushed);

hsm.dispatch(CoinInserted);

hsm.dispatch(CoinInserted);

hsm.dispatch(BarPushed);

}

This is the terminal output:

Event: 1 received

Self transition Locked->Locked

Event: 1 received

Self transition Locked->Locked

Event: 0 received

Transition Locked->UnLocked

Event: 0 received

Self transition UnLocked->UnLocked

Event: 1 received

Transition UnLocked->Locked

Let’s break the example:

First, we have a number of “event handlers” in this case also known as global functions, but because of the Action_t type it’s really a Delegate of type void(int) you can bind global functions or class methods. The event handler receives a parameter that is the event ID number that is defined in the Event enumeration, this enables to use the same event handler for all events in the same state and internally handle each case.

Hierarchical State Machine

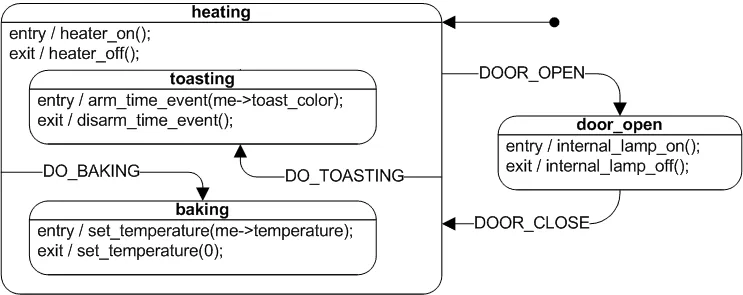

Now I will present an Oven controller example that will be used to show the hierarchical part of the machine. The example was taken from the Wikipedia article about UML state machines.

This controller uses two top-level states: DoorOpen and Heating, and is a really dumb oven the only way that you can keep it off is by open the door. The Heating state has two subStates: Toasting and Baking, the main difference is that the toasting process is at a fixed temperature with a timer, and when baking you can set the temperature value.

The UML design uses the entry/exit handlers as the outputs of the state machine. In this case, I used the state’s signalEntered and signalExited, I also could subclass the State class and override the onExit and onEntry virtual methods.

Here is the code:

#include "../../Include/HierarchicalStateMachine.hpp"

#include <stdio.h>

using namespace eHSM;

void InternalLampOn() { printf("InternalLampOn\r\n"); }

void InternalLampOff() { printf("InternalLampOff\r\n"); }

void HeaterOn() { printf("HeaterOn\r\n"); }

void HeaterOff() { printf("HeaterOff\r\n"); }

void ArmAlarm() { printf("Arm toasting alarm\r\n"); }

void DisarmAlarm() { printf("Disarm toasting alarm\r\n"); }

void SetBakingTemperature() { printf("Baking\r\n"); }

void TurnOffBaking() { printf("Not Baking\r\n"); }

int main() {

enum Events { DoorOpen, DoorClose, DoToasting, DoBaking };

const int DOOR_OPEN_STATE_EVENTS = 1;

const int HEATING_STATE_EVENTS = 3;

const int TOASTING_STATE_EVENTS = 1;

const int BAKING_STATE_EVENTS = 1;

Declare::State<DOOR_OPEN_STATE_EVENTS> doorOpenState;

Declare::State<HEATING_STATE_EVENTS> heatingState;

Declare::State<TOASTING_STATE_EVENTS> toastingState;

Declare::State<BAKING_STATE_EVENTS> bakingState;

HierarchicalStateMachine hsm;

// Connecting Entering and Exiting Signals

doorOpenState.signalEntered.connect<InternalLampOn>();

doorOpenState.signalExited.connect<InternalLampOff>();

doorOpenState.addEvent(DoorClose, heatingState);

heatingState.signalEntered.connect<HeaterOn>();

heatingState.signalExited.connect<HeaterOff>();

heatingState.addEvent(DoorOpen, doorOpenState);

heatingState.addEvent(DoToasting, toastingState);

heatingState.addEvent(DoBaking, bakingState);

toastingState.signalEntered.connect<ArmAlarm>();

toastingState.signalExited.connect<DisarmAlarm>();

toastingState.setSuperstate(heatingState);

bakingState.signalEntered.connect<SetBakingTemperature>();

bakingState.signalExited.connect<TurnOffBaking>();

bakingState.setSuperstate(heatingState);

hsm.setInitialState(heatingState);

hsm.start();

hsm.dispatch(DoorOpen);

hsm.dispatch(DoorClose);

hsm.dispatch(DoToasting);

hsm.dispatch(DoorOpen);

hsm.dispatch(DoorClose);

hsm.dispatch(DoBaking);

hsm.dispatch(DoorOpen);

}

This is the terminal output:

HeaterOn

HeaterOff

InternalLampOn

InternalLampOff

HeaterOn

Arm toasting alarm

Disarm toasting alarm

HeaterOff

InternalLampOn

InternalLampOff

HeaterOn

Baking

Not Baking

HeaterOff

InternalLampOn

The order of the dispatched events is DoorOpen, DoorClose, DoToasting, DoorOpen, DoorClose, DoBaking and DoorOpen.

Let’s analyze the terminal output vs the dispatch order, the initial state it’s Heating so when the state machine is started the Heating onEnter signal is triggered which prints HeaterOn in the terminal. Then the DoorOpen event is dispatched triggering the onExit signal of the Heating state and the onEnter signal from the DoorOpen state. The rest of the events have a similar flow.

- Initial State: Heating State -> OnEnter -> HeaterOn

- Event DoorOpen: Heating State -> OnExit -> HeaterOff -> DoorOpen State -> OnEnter -> InternalLampOn

- Event DoorClose: DoorOpen State -> OnExit -> InternalLampOff -> Heating State -> OnEnter -> HeaterOn

- Event DoToasting: Toasting State -> OnEnter -> Arm toasting alarm

- Event DoorOpen: Toasting State -> OnExit -> Disarm toasting alarm -> Heating State -> OnExit -> HeaterOff -> DoorOpen State -> OnEnter -> InternalLampOn

- Event DoorClose: DoorOpen State -> OnExit -> InternalLampOff -> Heating State -> OnEnter -> HeaterOn

- Event DoBaking: DoBaking State -> OnEnter -> Baking

- Event DoorOpen: DoBaking State -> OnExit -> Not Baking -> Heating State -> OnExit -> HeaterOff -> DoorOpen State -> OnEnter -> InternalLampOn

Deus Ex Machina (as Conclusions)

Using a library for a state machine implementation is a superior experience when compared with switch-case or spaghetti-code patterns. It has a sort of preamble with the states and states machine instantiations, but it’s easy to read, at least when compared with the alternative.

This particular library allows implementation of UML state machines and the hierarchical ones, exposes the onEnter and onExit signals to be use as the output of the state machine. It also has the method State::addEvent which has 3 overloads:

addEvent(EventId_t event, State &nextState, Action_t &action)addEvent(EventId_t event, State &nextState)addEvent(EventId_t event, Action_t &action)

You can handle an event with a transition with an action, with a transition without an action, and with an action without a transition. This, with the onEnter and onExit signals, offers the most flexible options in order to implement the desired functionality in a particular state.

I hope that this will be useful to you dear C++ embedded developer.